I just happened to stick my head up from the books for a moment to catch a wild discussion taking place on Twitter about whether 3D mash-ups of masterpieces are ‘sacrilege’ or merely ‘winking irreverence’. Arts journalist Lee Rosenbaum Tweets that the ‘@MetMuseum‘s digerati should serve the curators, not the other way around’, and is clearly troubled by moves within the museum to enable artists and others to create new types of art from the digital bodies of old ones.

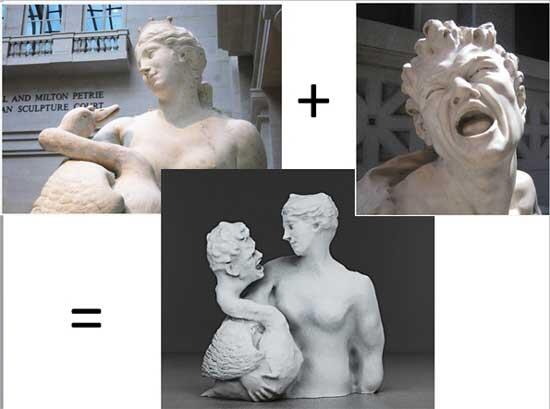

A stake are mashups like this version of Leda and the Swan hacked together with Marsyas, by Jon Monaghan (which I have to confess that I love, and am terrified by).

I am so glad Rosenbaum has raised these questions, because to me they are actually about very core issues at the heart of contemporary museology, and no doubt speak to bigger issues than one short Twitter conversation. Is the museum’s core role and responsibility to protect sacred cows from those who question them (even though questioning can equally be an act of exaltation as irreverence)? Or is it to enable humankind to draw on those ideas and objects from the past considered worthy of recognition, protection, and value, in order to create something new, and to come up with new ways of asking questions and seeing the world? Are museums about now, and responses to a changing world, or an attempt to freeze in time as much as possible those things which are from a world that has already shapeshifted away? Is it more disrespectful to a work of art (and the artist who once created it) to enable these kinds of digital mash-ups that bring the work into a contemporary context and conversation, or to prevent them? And does a 3D mash-up of multiple works of art actually lesson the relevance or importance of the original work? Is Leda and the Swan now less magnificent for the fact that it has been reimagined through a new technology, and with a new face?

Liz Neely and Miriam Langer published a useful paper at Museums and the Web this year, on the emergence of 3D printing and scanning, in which they argue that the act of 3D modelling offers museum visitors the capacity to gain insight into an object:

To create a 3D model of the object, the visitor must photograph it from every angle, requiring a close examination and consideration of the object’s form. To create a really good 3D scan without massive distortion, the photographer must look carefully at the artwork, think about angles, consider shadows, and capture all physical details. This is just the kind of thought and ”close looking” we want to encourage in the museum. When a photogrammetric model is unsuccessful, even this failure can initiate a point of dialogue. What caused this failure? Was it a missed angle? Are areas lost in shadow? Is the shape too amorphous? The failed model may provide a surprising launch pad from which to celebrate a derivative “glitch” creation. Glitches and other unintended transformations are prevalent because the freely available 3D creation tools are young and evolving.

This perspective would position the fun of 3D absolutely in support of the original object, even if later results aren’t faithful to its prototypical intentions.

In some ways, I think that the technology question here is a bluff; a distraction. Haven’t artists always questioned the work of other artists, simultaneously nodding at their importance and interrogating it? Isn’t this, in fact, part of what makes art such an interesting (and often insidery) game; these long-running conversations about materiality and culture, that utilise the same objects and symbols from one generation to the next; that pull apart the ideas of one another in a critique? Is not art, after all, as much about a response to its own history as to the conditions that surround it?

Or is the problem the fact that it isn’t just artists making these works; that it might be a museum technologist who asks questions of the work, just as much as another artist? Or a programmer with no traditional artistic background or impulse? I am perhaps as concerned about the notion that a museum’s ‘digerati’ should serve the curators, not the other way around as I am about the privileging the masterpiece over new creation. Firstly, it imagines that somehow a 3D mashup of a work of art necesssarily does not serve the curators (or artist). But it also creates a false dichotomy through which to think through the relationship between the curator and digital technologies.

Digital technologies are becoming more and more knit into not just how we operate online, but how we perceive and experience in the world far more broadly. I met an artist last year who photographs her paintings every time she works on them, not as a way to track their progress, but so that she can see what they look like when viewed digitally via a screen, since that will primarily be the way her works are experienced. Her artistic processes are driven and changed in response to the digital context through which art and ideas are communicated. This is the circumstance in which culture now exists. And just like artists, curators themselves do and must serve digital demands as much as physical ones. The relationship is not hierarchical.

And I wonder if this isn’t at the crux of this whole discussion; about the shift in the balance of power as traditional artforms and positions are interrogated. I’ve been writing a lecture this morning on art and digital technology, which led me to revisit Will Wiles’ 2012 piece on The New Aesthetic. In it, he speaks of how the intent of The New Aesthetic was to draw attention to the fluctuations in power relationships, in response to ‘the riotous spread of new technologies of seeing.’ He includes a quote from James Bridle, that seems pertinent here (though you should go and read it in context too):

‘The programmers have a huge amount of agency in the world, because they can deconstruct, reverse engineer and write and construct and create these systems. People who can’t, don’t, and they have less power in the world because of it.’

I wonder whether what’s at stake is not so much the interrogation of the art object, but the agency of those who do and don’t have the power to participate in these discourses?

What do you think? Is the concern about irreverent mashups of important works of art simply a response to shifts in power, and reduced agency, or does it speak to a genuine problem about the sacredness of art? What am I missing in thinking through this issue? I’d love your thoughts.

Note: Koven beat me to this discussion with his own short piece. Check it out here.